Genetically altering heart muscle cells to make them regulate heart rate could be an alternative to implanting electronic pacemakers, according to a study in pigs reported in the 16 July issue of Science Translational Medicine.

If proven to work in humans, this “biological pacemaker” approach could be applied in cases where people need an electronic pacemaker but can’t get one. This includes adults who develop life-threatening infections after pacemaker implantation and need to have their devices temporarily removed, or fetuses with congenital heart block, a condition that often results in stillbirth.

“This development heralds a new era of gene therapy where genes are used not only to correct a deficiency disorder, but actually to convert one kind of cell into another type to combat disease,” said co-author Eduardo Marbán, director of the Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute in Los Angeles, California.

Electronic pacemakers, a billion-dollar industry, are implanted devices hooked up to the heart to monitor heartbeat rhythm. They work by sending electrical pulses to the heart if it is beating too slowly or if it misses a beat. Healthy hearts without pacemaker hardware depend on naturally occurring pacemaker cells housed in a tiny region of the heart called the sinoatrial node (SAN) for this function. The SAN acts like a metronome to keep the heart pulsing at 60-90 beats per minute. People with abnormal heart rhythms lose the SAN function.

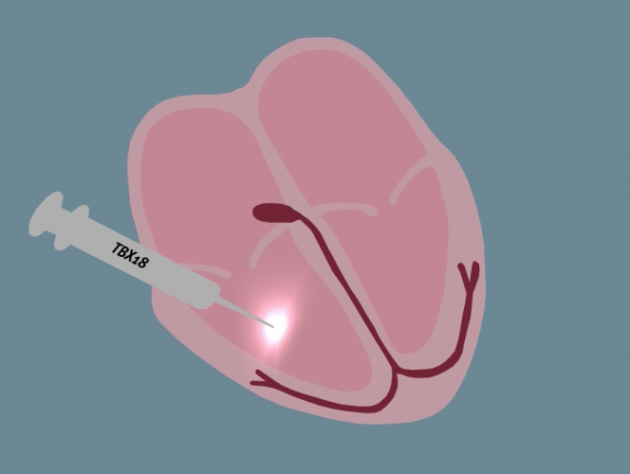

Marbán and colleagues converted a tiny area of heart tissue not normally involved in initiating heartbeats into a population of pacemaker cells that regulates heart rate. To achieve this feat, the researchers injected a gene called TBX18 — which expresses a protein that makes the heart keep rhythm — into the hearts of pigs with a condition known as complete heart block. “Before the treatment,” Marbán explained, “these animals’ heart rates were abnormally low, at about 50 beats per minute.”

Putting the gene into their heart tissue changed some of their heart muscle cells into SAN cells, however. “In essence,” Marbán said, “we created a new sinoatrial node in a part of the heart that ordinarily spreads the electrical impulse, but does not originate it.”

The procedure increased the diseased pigs’ heart rates to 70-90 beats per minute, a normal range. It did this without the need for an electronic pacemaker, and protection lasted two weeks.